NODE-BASED SCENARIO DESIGN PART 5: ALTERNATIVE NODE DESIGNS

|

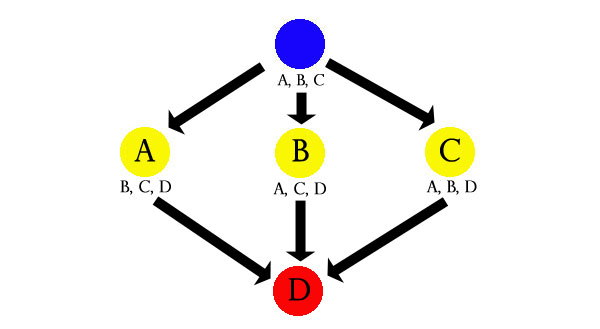

On the other hand, there is something to be said for the Big Conclusion. There are plenty of scenarios that don’t lend themselves to a shuffling between nodes of equal importance: Sometimes Dr. No’s laboratory is intrinsically more important than Strangeways’ library. And the Architect’s inner sanctum requires the Keymaker. So let’s talk about some alternative node structures.

CONCLUSIONS  In this design, each node in the second layer contains a third clue that points to the concluding node D. The function should be fairly self-explanatory: The PCs can chart their own course through nodes A, B, and C while being gently funneled towards the big conclusion located at node D. (Note: They aren’t being railroaded to D. Rather, D is the place they want to be and the other nodes allow them to figure out how to get there.) One potential “problem” with this structure is that it allows the PCs to potentially bypass content: They could easily go to node A, find the clue for node D, and finish the adventure without ever visiting nodes B or C. Although this reintroduces the possibility for creating unused content, I put the word “problem” in quotes here because in many ways this is actually desireable: When the PCs make the choice to avoid something (either because they don't want to face it or because they don't want to invest the resources) and figure out a way to bypass it or make do without it, that's almost always the fodder for an interesting moment at the gaming table in my experience. Nor is that content "wasted" -- it is still serving a purpose (although its role in the game may now be out of proportion with the amount of work you spent prepping it). Therefore, it can also be valuable to incentivize the funneling nodes in order to encourage the PCs to explore them. In designing these incentives you can use a mixture of carrots and sticks: For example, the clue in node A might be a map of node D (useful for planning tactical assaults). The clue in node B might be a snitch who can tell them about a secret entrance that doesn’t appear on the map (another carrot). And node C might include a squad of goons who will reinforce node D if they aren’t mopped up ahead of time (a stick). (That last example also shows how you can create multi-purpose content. It now becomes a question of how you use the goon squad content you prepped rather than whether you’ll use it.)

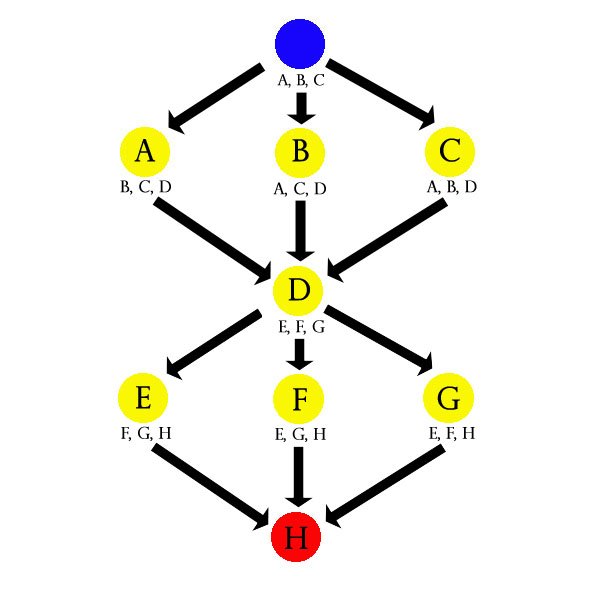

FUNNELS The basic structuring principles of the conclusion can be expanded into the general purpose utility of funneling:

Each layer in this design (A, B, C and E, F, G) constitutes a free-form environment for investigation or exploration which gradually leads towards the funnel point (D or H) which contains the seeds leading them to the next free-form environment. I generally find this structure useful for campaigns where an escalation of stakes or opposition is desirable. For example, the PCs might start out investigating local drug dealers (A, B, C) in an effort to find out who’s supplying drugs to the neighborhood. When they identify the local distributor (D), his contacts lead them into a wider investigation of city-wide gangs (E, F, G). Investigating the gangs takes them to the Tyrell crime family (H), and mopping up the crime family gets them tapped for a national Mafia task force (another layer of free-form investigation), culminating in the discovery that the Mafia are actually being secretly run by the Illuminati (another funnel point). (The Illuminati, of course, are being run by alien reptoids. The reptoids by Celestials. And the Celestials by the sentient network of blackholes at the center of our galaxy. The blackhole consciousness, meanwhile, has suffered a schizord bifurcation due to an incursion by the Andromedan Alliance…. wait, where was I?) In particular, I find this structure well-suited for D&D campaigns. You don’t want 1st-level characters suddenly “skipping ahead” to the mind flayers, so you can use the “chokepoints” or “gateways” of the funnel structure to move them from one power level to the next. And if they hit a gateway that’s too tough for them right now, that’s OK: They’ll simply be forced to back off, gather their resources (level up), and come back when they’re ready. Another advantage of the funnel structure is that, in terms of prep, it gives you manageable chunks to work on: Since the PCs can’t proceed to the next layer until they reach the funnel point, you only need to prep the current “layer” of the campaign.

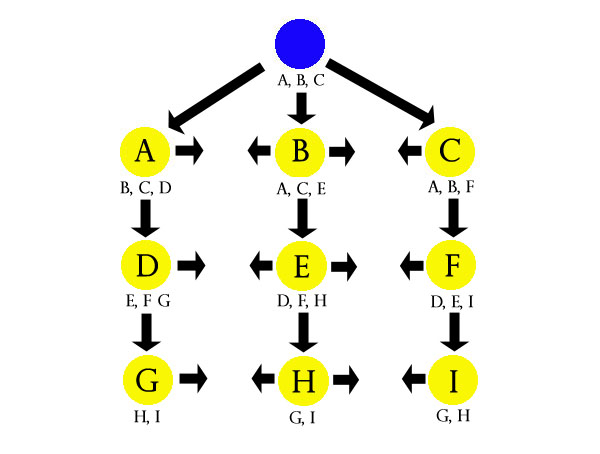

LAYER CAKES

A layer cake design achieves the same general sense of progression that a funnel design gives you, but allows you to use a lighter and looser touch in structuring the scenario. The most basic structure of the layer cake is that each node in a particular “layer” gives you clues that lead to other nodes on the same layer, but also gives you one clue pointing to a node on the second layer. Although a full exploration of the first layer won’t give the PCs three clues to any single node on the second layer, they will have access to three clues pointing to a node on the second level. Therefore, the Inverted Three Clue Rule means that the players will probably get to at least one node on the second layer. And from there they can begin collecting additional second layer clues. Whereas PCs in a funnel design are unlikely to backup past the last funnel point (once they reach node E they generally won’t go back to node C since it has nothing to offer them), in a layer cake design such inter-layer movement is common. Layer cakes have a slightly larger design profile than funnels, but allow the GM to clearly curtail the scope of their prep work (you only need to prep through the next layer) while allowing the PCs to move through a more realistic environment. You’ll often find the underlying structure of the layer cake arising naturally out of the game world.

|

LARGE

LAYERS

In case it hasn’t been clear, I’ve been using three-node layers in these examples because it’s a convenient number for showing structure. But there’s nothing magical about the number. Each “layer” in the previous examples constitutes an interlinked environment (either literal or metaphorical) for exploration or investigation, and you can make these environments as large as you’d like. As long as each node has a minimum of three clues in it and a minimum of three clues pointing to it, the Three Clue Rule and its inversion will be naturally satisfied and guarantee you a sufficiently robust flow through the layer. But as you increase the number of nodes, you also open the possibility for varying clue density: Particularly dense clue locations could have six or ten clues all pointing in different directions. Obviously, however, the larger each layer is, the more prep work it requires.

DEAD

ENDS

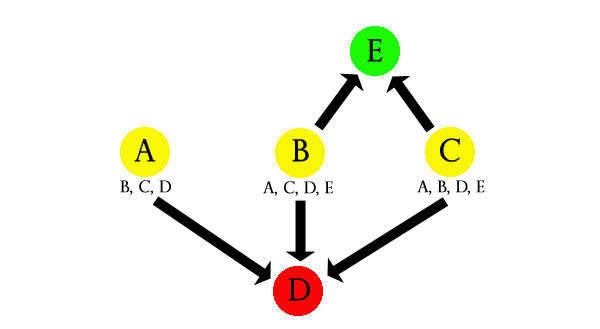

Dead ends in a plotted mystery structure are generally disasters. They mean that the PCs have taken a wrong-turn or failed to draw the right conclusions and now the train is going to crash into a wall: There should be a clue here for them to follow, but they’re not seeing it, so there’s nowhere to go, and the whole adventure is going to fall apart. But handled properly in a node-based structure, dead ends aren’t a problem: This lead may not have panned out, but the PCs will still have other clues to follow.

In this example, node E is a dead end. Clues at nodes B and C suggest that it should be checked out, but there’s nothing to be found there. Maybe the clues were just wrong; or the bad guys have already cleared out; or it looked like a good idea but it didn’t pan out into usable information; or it’s a trap deliberately laid to catch the PCs off-guard. The possibilities are pretty much limitless. The trick to implementing a dead end is to think of clues pointing to the dead end as “bonus clues”. They don’t count towards the maxim that each node needs to include three different clues. (Otherwise you risk creating paths through the scenario that could result in the PCs being left with less than three clues. Which may not be disastrous, but, according to the Inverse Three Clue Rule, might be.) On the other hand, as you can see, you also don’t need to include three clues leading to a dead end: It’s a dead end, so if the PCs don’t see it there’s nothing to worry about. Of course, if you include less than three clues pointing to the dead end then you’re increasing the chances that you’re prepping content that will never be seen. But this also means that the discovery of the dead end might constitute a special reward: Extra treasure or lost lore or a special weapon attuned to their enemy. Which leads to a broader point: Dead ends may be logistical blind alleys, but that doesn’t mean they should be boring or meaningless. Quite the opposite, in fact. In the same vein as dead ends, you can also use “clue light” locations. (In other words, locations with less than three clues in them.) Structurally such locations generally work like dead ends, by which I mean that clues pointing to clue light locations need to be “bonus clues” to make sure that the structure remains robust. The exception to this guideline is that you can generally have a number of two-clue locations equal to the number of clues accessible in a starting node. (For example, in the layer cake structure diagram you have three nodes in the bottom layer with only two clues each because the starting node contains three clues. If there wasn’t a starting node with three clues in it, the same structure would have potential problems.)

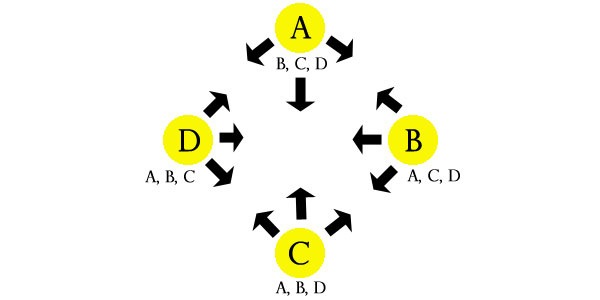

LOOPS

In this simple loop structure all four nodes contain three clues pointing to the other three nodes. The advantage of this simple structure is that the PCs can enter the scenario at any point and navigate it completely. Obviously, this is only useful if the PCs have multiple ways to engage the material. In a published product this might be a matter of giving the GM several adventure hooks which can be used (each giving a unique approach to the adventure). In a personal campaign, clues for nodes A, B, C, and D might be scattered around a hexcrawl: Whatever clues the PCs find or pursue first will still lead them into this chunk of content and allow them to explore it completely. |

| GO TO PART 6 |